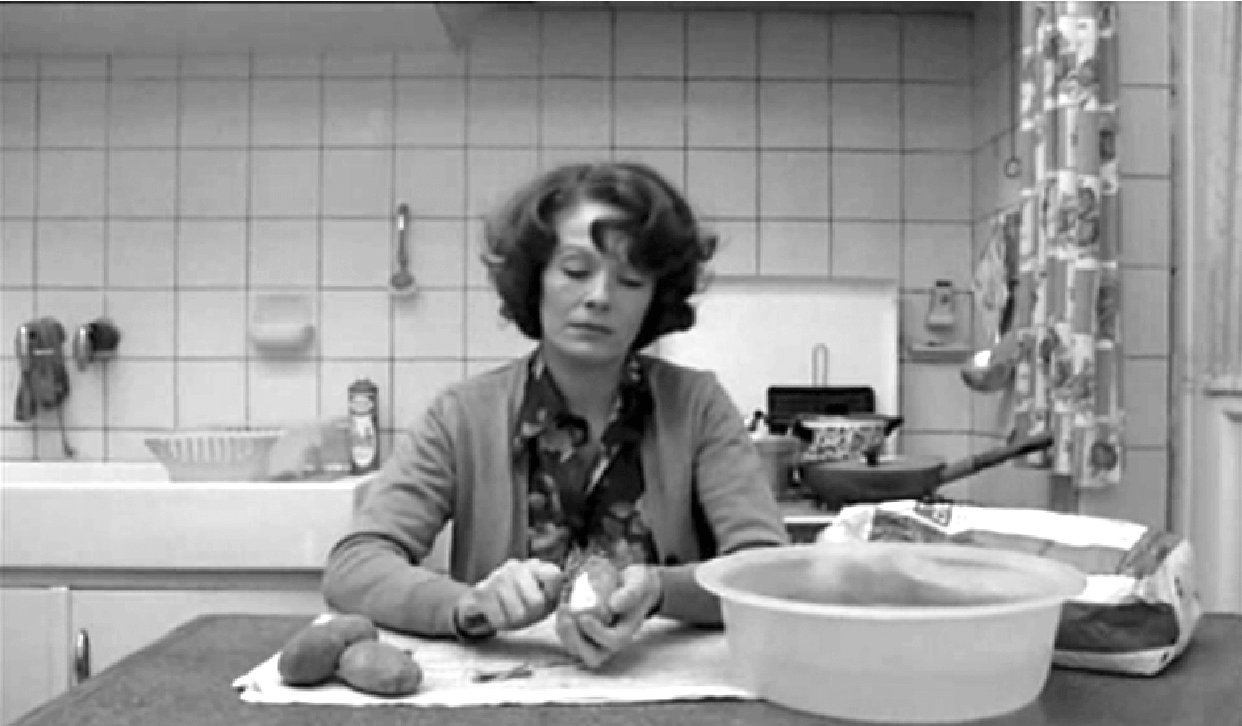

Still image from Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

On the 6th of October 2015 Chantal Akerman, the Belgian filmmaker and artist, put an end to her life. Akerman’s unexpected death kindled a discussion around her films, many of which dwell on the consequences of a life lived enclosed in domestic spaces. In such spaces women’s bodies are subjugated to the performance of domestic routine. Their pain, the result of long, slow marginalisation, becomes an integral part of everyday life. In the aftermath of her death, various commentaries flashed up on social media alluding to her history of depression. And inevitably this context seemed to lend added urgency to her work, which persistently demands we look closer at images attesting to a routinised pain that is too often left unaccounted for. Akerman’s films contemplate the capacity to live where death lingers in waiting. And typically, when death does feature, it is far from any dramatic event, rather it appears painfully banal.

Recall Jeanne Dielman, sitting at the kitchen table, peeling potatoes endlessly, killing time. What is her body waiting for? Is Jeanne Dielman peeling the potatoes in the hope that this tedious routine may, eventually, come to an end? Or is she destined to remain confined to the domestic sphere and its repetitious labour, enacting a kind of involuntary ‘house arrest’? Her behaviour poses a crucial question: is there a way to live in the present when the future is closed off?

Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), focuses on the life of a single mother who is tied into a schedule of cooking and cleaning. As if nothing more than another chore, she also prostitutes herself, inviting men into her house on a daily basis. Jeanne Dielman, like many of Akerman’s films, confronts the viewer with a sense of never-ending anticipation, of always waiting for the slightest change that may or may not unfold on screen. The body is a surface upon which time slowly inscribes itself, carving ever deeper into the flesh with the persistent gaze of a camera that observes patiently and tirelessly to a point of excess. The gaze of Akerman’s camera does not flinch, and as we follow the minor gestures of the body, the image is only interrupted by the blinking of the human eye. Perhaps her body can no longer wait, and indeed, when the future is closed-off, she is no longer killing time but rather it is time that kills her.

However, her routine is interrupted when Jeanne picks up a pair of scissors and buries them deep into the neck of her client – a man who lies naked in her bed. With this gesture, confinement takes its deadly toll. In this single murderous act, ‘dead time’ is suddenly pierced by an event that has the potential to change her life forever. Yet nothing out of the ordinary occurs – no change in shot distance or editing pace, and no blood, struggle or graphic display. The scene is filmed with the same fixed-frame shot that previously captured Jeanne peeling potatoes and preparing meatloaf. The murder, the most explicit evidence of Jeanne’s desperation, is still contained within the restrained cinematic grammar that was so well suited to her earlier, routine behaviour.

The violence of the stabbing is not only directed at the neck of the man lying in the bed; it is a blow to a dull and monotonous life of repetition, a seismic break with domestic maintenance and the habits it inscribes. Jeanne Dielman’s action seems premeditated and well-planned; it is a reaction not only against the masculine gaze that placed her there, as has often been suggested, but also against the economy of the household.1 This economy works to depoliticise the body and to reduce it to its mere biological existence, manifested here through the preparation of meals, cleaning the house and fulfilling the sexual needs of various men. It also forces the body to work in the all-consuming privacy of the home. Hannah Arendt famously claimed that “To live an entirely private life means above all to be deprived of things essential to a truly human life.”2 Domestic enclosure represents privacy in its most repressive form, in which the home ceases to be a site of belonging and becomes a set of physical borders within which the basic conditions of life are closely monitored. It is a space of detention; and crucially it normalises the docility of the body, which is stripped down to its mere physicality and daily habits. After all, what is ‘habit’ if not the flattening of events through endless repetition?

Israa Abed

On the day that Chantal Akerman died, news agencies worldwide covered a wave of violence between Palestinians from East Jerusalem and the West Bank and the Israeli authorities. One headline in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz ran: ‘East Jerusalem’s Leading Role in Terror Attacks Catches Israel Off Guard.’3 What began as a single incident in the Old City of Jerusalem quickly escalated into a spree of sporadic violence; Palestinians attempted to stab Israelis using whatever sharp instruments they could lay their hands on. While the Israeli mainstream media speculated about the origins of the violence and debated whether a third Intifada was on its way, it became clear that this was not a single event or a planned insurgency but rather a series of uncoordinated actions arising from an extended period of enforced segregation and deep control of all forms of life under occupation – acts of desperation which for some reason still catch Israel ‘off guard’.

A screenshot from YouTube of a video depicting Israa Abed moments before she was shot at the Afula bus station on the 9th October 20154

It is precisely the apparent spontaneity of these isolated assaults by solitary men and women that disoriented the Israeli mainstream media. Short video clips and snapshots caught on security and smartphone cameras, then distributed through social media, showed Palestinian individuals in the act of stabbing – or trying to stab – policemen and civilians. The clips also documented the deaths of Palestinians by Israeli gunfire. The violence was made visible through numerous pixelated and ambiguous video clips depicting events taking place in public spaces: a busy crossroad, a central bus station, a main street. The fingers of Israeli soldiers, police and in some cases civilians were quick on their triggers, ready to shoot down anyone displaying the ‘symptoms’ of terror. Confronting terror, as is widely accepted in Israeli society, means reacting quickly and severely.

While Jeanne Dielman’s image was circulated on social media as a way of commemorating Akerman’s death, she was also momentarily reincarnated on our screens through the image of Israa Abed, a young Palestinian woman who stood still in the middle of a busy bus station holding a kitchen knife in her hand before being shot and injured by a local security man. Preliminary investigations suggested that Israa Abed had intended to carry out an attack, but as the full details of the event were revealed, it was concluded by an Israeli court that, in fact, she had intended to trigger a violent response from the authorities and get herself killed. Israeli media claimed it was an attempt at suicide, after which the case was closed, the court concluding that a temporary mental breakdown had probably taken hold of her. Indeed, the video clip itself could attest to such conclusions. Standing still, kitchen knife in hand, Abed enacted a drama that would likely lead to her immediate death: becoming the image of terror.

Whereas on other occasions knives were used as weapons, here the act of brandishing a knife in a heavily surveilled bus station was later understood as Abed’s way of getting herself shot: a performance of terror with the aim of committing suicide. Holding the kitchen knife and stretching out her arm, Abed’s body became instantly visible, drawing the attention of all cameras and eyes around her. In her bright green hijab, her body was already marked-out, spectacularly visible, even as it fell to the asphalt below. On the one hand, visual evidence showed that Israa Abed did not attempt to stab anyone. She was simply standing there, frozen in her place, showing no signs of threat. On the other, her appearance – a hijab, the kitchen knife – instigated a violent response. With this in mind, ‘terror’ could be defined as an aesthetic category that disrupts the existing order of the sensible: an image of violence that intervenes in the existing distribution of power defined by what and who is publicly visible and who is systematically ‘out-of-frame’. It is an act that draws the cameras as well as gunfire. It challenges a particular, prescribed visibility that takes control of the body. By framing the body in such a way that it destabilises this order, an image of terror is produced, one that provokes an eruption of violence.

For Jacques Rancière, political action is precisely that which challenges the existing social and aesthetic order, an order that “destines specific individuals and groups to occupy positions of rule or of being ruled, assigning them to private or public lives, pinning them down to a certain time and space, to specific ‘bodies’, that is to specific ways of being, seeing and saying.”5

Hence the act of ‘breaking routine’ with the aid of a kitchen knife or a pair of scissors becomes the restaging of a domestic gesture as political action, bridging the deep divide between the private and the public. In this way, the domesticated image of the body is ‘publicised’, exteriorising domestic labour and transforming it into an expression of pain – no longer radically individualised, but public and exemplary. It makes the pain of domestic confinement visible, and not only in the perceptual sense. Making the invisible visible entails circumventing a given order of perception, politicising it and hence revealing its repressive logic.

In their anonymity, both Israa Abed and Jeanne Dielman challenge how the body is subjected to a particular image. They challenge what Nicholas Mirzoeff calls ‘visuality’: “visuality segregate[s] those it visualize[s] to prevent them from cohering as political subjects, such as workers, the people, or the (decolonized) nation […] it makes this separated classification seem right and hence aesthetic.”6 Both Israa Abed’s and Jeanne Dielman’s interventions adopt the same forms of visualisation that initially classified them as docile. In fact, they take this visualisation to a point of excess, suddenly turning it against the authority that engendered and sustained it.

Images distributed by various media sources and described as weapons used by Palestinians during the 2015 ‘Knife Intifada’

The images of Israa Abed and Jeanne Dielman are an uneasy pairing. The two belong to extremely different image regimes. Yet when juxtaposed they seem to form only a small part of a collage, extending in all directions, of bodies with kitchen knives in their hands. They demand that we see what is continually erased. They attack systems of visualisation that exclude them from all forms of political engagement; and in doing so, they become political. The everyday gesture mutates into an act of violence; the image of the body as a site of discipline refuses to adhere to its confinement. These disparate bodies are aligned through their sudden yet premeditated disruption of routine. They pose a countervisuality by turning the body against the gaze that continually and persistently disarms their political charge. Perhaps this is what the Israeli state sees as a new form of terror.

Petrified Homes

During October 2015 the Israeli police circulated photographs of weapons that were found next to the bodies of Palestinian assailants on the streets of Israeli cities. These taxonomic-forensic images presented a catalogue of kitchen knives, potato peelers and screwdrivers placed one next to the other. As the Israeli army (IDF) or police traced these weapons back to their supposed place of origin, they were led to the domestic realm, conceived by the Israeli authorities as the source of terror. Anthony Vidler suggests that domestic spaces are presumed to hide, in their darkest recesses and forgotten margins, all the objects of fear and anxiety that continually return to haunt the imagination.7 As such, the interior spaces of Palestinian homes are often perceived by the Israeli security forces as extensions of the body of the terrorist – in all its malaise and aberrance. Taking control over the ‘unruly’ body of the terrorist therefore means taking over the home that it inhabited.

The 2015 ‘Knife Intifada’, as it was dubbed by the Israeli media, should perhaps be renamed the ‘Kitchen Knife Intifada’, bearing in mind the knives, scissors, potato peelers and screwdrivers that the attackers used as weapons. But a ‘Kitchen Knife Intifada’ is not only about weaponising the domestic object; more fundamentally, it is about how the Israeli occupation and its military rule are consolidated at the level of the domestic, and its particular ‘politics of life’ – a politics that constricts and attacks the household economy as a technique of governance.8 Moreover this governance is exercised through a particular domestic ‘visuality’, that is through the various ways in which authorities imagine domesticity and present it as a series of images. Indeed, a timeline of the events of October 2015 could be constructed entirely out of photos and video clips taken by Israeli soldiers in or on the way to the homes of alleged terrorists. When tracing how the Israeli authorities perceive security threats, the private interiors of homes appear as a constant source of danger. Conceived as a place of belonging (and belongings), the home of the assailant provides an address and a space for the IDF to raid or destroy. By perpetuating this view, the IDF invokes the traditional conception of the home as the extension of the body and the realm of biological existence. The blame for the acts of an individual is transferred onto his or her family members who all inhabit the same house, and in turn the very structure of the home is attacked, including those who dwell within it. What begins with the Israeli authorities taking control over the home ends with their intrusion into the domestic space itself, which is understood as the source of terror.

The link between domestic imaginaries and terror is not new. In the aftermath of the 1967 war Israel implemented the Defence Emergency Regulations (DERs) that were initially put in place under the British Mandate. Under these regulations, military commanders possess a wide range of discretionary powers, including the authority to order house demolitions and deportations, to impose curfews and to arrest, search and detain persons suspected of posing a threat to public order, without prior judicial approval. In addition, the ‘state of emergency’ declared by the Provisional State Council on the 19th May 1948 remains in effect to this day; this situation enables the government to alter or suspend laws passed by the elected legislature. Yifat Holzman-Gazit writes that “the provisional government in the summer of 1948 issued emergency Requisition of Property regulations, which permitted government officials to take immediate possession of private property, Jewish as well as Arab, in order to further, first and foremost, the defense of the State.”9 The demolition of houses, expulsion and arrest without trial were the most common uses of the regulations. The adoption of such laws embedded, literally and legally, a ‘state of emergency’ into the very fabric of the Israeli occupation.

According to the NGO B’Tselem, on the 6th of October 2015 – the day of Chantal Akerman’s death – the IDF accelerated demolition after a period of relative quiet. Two housing units were destroyed in East Jerusalem and another filled with cement as a response to attacks perpetrated by the relatives of the people living in these homes.10 Furthermore, in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Jabal al-Mukaber, the IDF blew up the home of Nadia Abu al-Jamal, the widow of Ghassan Abu al-Jamal, a man who killed four Jewish civilians and wounded seven others in November 2014. (Ghassan Abu al-Jamal himself was killed in a shootout with police officers at the time of the attack.) On that same day, in Abu Tur, soldiers sealed a room with cement in the family home of Mu’taz Hijazi, who had seriously injured right wing Jewish activist Yehuda Glick in 2014. The sealed room had been occupied by one of his brothers. These authorised acts of collective punishment were also timed to intimidate anyone living nearby who might be ‘inspired’ by their neighbours. Such procedures targeting the homes of perpetrators have a long history and highlight the central position of the house or the home as a site of collective discipline and punishment in the case of Israel and Palestine.

A photograph taken by Amnesty International frames the interior space of the ‘sealed’ house in Abu Tur. “To seal a room,” an Amnesty correspondent writes, “the Israeli authorities break a window, insert a hose from a cement mixer, and pump cement into the house.”11 ‘Force-feeding’ the interior with as much as ninety tons of cement, the space is cast in solid material, in an uncanny echo of the construction process. Yet, as the image clearly attests, the objective of this perverted construction is to make the interior spaces uninhabitable; to drown the space in the very material it was constructed from.

A ‘sealed’ home in Abu Tur, October 2015, Jacob Burns/Amnesty International

In contrast to physical destruction, the act of ‘sealing’ leaves the exterior of the house intact. Rather than destroying the walls and rooftops that mark the edges of a given space, sealing obliterates space by preventing any potential movement within it, literally occupying every last centimetre. One can imagine the occupying power materialising itself as cement, breaking in through the windows and doors and flooding the home with its presence. As such, ‘sealing’ is a form of destruction that eradicates the private realm; it eats up space and expels the bodies that can no longer move within it. It attacks and erases the very conditions of domestic life.

The destruction of a house, whether by sealing or demolition, should not be seen merely as an act of collective punishment but as the destruction of the ability to imagine a life at home, one that offers the shelter, intimacy and privacy that an ideal ‘home’ ensures. Only by tracing the path that leads the Israeli authorities back to the homes of Palestinians can we comprehend the far-reaching involvement of the IDF in the private lives of people living under occupation in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

Destroying homes, a violation of international law, is justified by the Israeli judicial system in terms of a strategy of deterrence that shifts the responsibility of the individual onto his or her family members. Leaning on a colonial perception that naturalises the family as the core of Palestinian life, the Israeli state perpetuates attacks against the families of alleged terrorists on the presumption that family members must take responsibility for the actions of their young relatives. This is a case of culturalism that treats the Palestinian population as ‘one big family’, thereby collectivising acts of violence.

When addressing why demolitions are never carried out in response to attacks by Jewish terrorists, such as those who murdered Muhammad Abu Khdeir or those who torched the home of the Dawabshe family, the Israeli Supreme Court argues that these are isolated and exceptional acts of violence. Justice Noam Sohlberg explains why such measures are used specifically against Palestinians by arguing that, since in “traditional Palestinian society, the family occupies a central space”, placing pressure on the family can be an effective form of intervention.12 This perception, articulated by one of the highest-ranking judges of an occupying power, illustrates the sweeping socio-cultural assumptions actively deployed to govern and control a population under military occupation – at the same time asserting the moral supremacy of the ruling group. Such colonial perspectives gather together Palestinians as a single collective or ‘family’, imagining the home or the house as the enemy’s stronghold. The body of the terrorist – shot dead while attempting to stab a Jewish civilian or soldier – seemingly operates in the name of the family to whom he or she belongs. By tying that body to the realm of the home, it is naturalised, no longer acting as its own agent but in the name of an indeterminate family that must take responsibility for its acts.

Against governing perceptions that fix the body in its ‘natural’ place, binding it to its habits and domestic routines, Israa Abed and Jeanne Dielman – each in their own way – show us the urgency of questioning and challenging the hierarchies that divide bodies, marking some as protected and others as precarious. By linking this demand back to the domestic realm, they expose an apparatus that tends to remain undetected and invisible – a so-called ‘home’ – defined not merely as a set of walls and doors but as a sphere of socio-political determination, too often deemed natural in order to justify an ongoing and systematic denial of rights. The images of Israa Abed and Jeanne Dielman hold out against such systems of exclusion that separate the domestic and public realms.

At one level Israa Abed and Jeanne Dielman are, of course, incomparable. Jeanne Dielman, after all, is a character in a fictional narrative. But their body-images, detached from any corporeality, momentarily converge to perform for the camera what their muted voices cannot tell. As images, both Abed and Dielman adapt and re-enact gestures taken from the lexicon of housekeeping, demonstrating them publicly, revealing the slow and suspended violence that makes domestic routine invisible in the shadows of interior spaces.

1. In a seminal essay, Laura Mulvey rejects the status that Hollywood narrative cinema has assigned to women, the status of “to be looked-at-ness”: “The first blow against the monolithic accumulation of traditional film conventions [...] is to free the look of the camera into its materiality in time and space and look of the audience into dialectics, and passionate detachment. There is no doubt that this destroys the satisfaction, pleasure and privilege of the ‘invisible guest’, and highlights how film has depended on voyeuristic active/passive mechanisms.” See Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, in Ann E. Kaplan, ed., Feminism and Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 47.

2. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd edition (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1958), p. 58.

3. Amos Harel, ‘East Jerusalem’s Leading Role in Terror Attacks Catches Israel Off Guard’, Haaretz, 17 Oct 2015 <http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.680771> [Accessed 18 May 2016].

4. Still from Haeemet Shelanu, ‘Terrorist want to murder Jewish civilians [sic]’, 14 October 2015 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Vb5FGpNzsU> [accessed 6 June 2016]. This is an approximate translation from the Hebrew.

5. Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (London: Continuum, 2004), p. 56.

6. Nicholas Mirzoeff, ‘The Right to Look’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Spring 2011), p. 476.

7. Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny (Cambridge MA: MIT press, 1994), p. 167.

8. Thomas Lemke, drawing on Michel Foucault, notes that “In addition to the management by the state or the administration, ‘government’ also signified problems of self-control, guidance for the family and for children, management of the household, directing the soul, and other questions.” To this Lemke adds that “Government refers to more or less systematized, regulated and reflected modes of power (a ‘technology’) that go beyond the spontaneous exercise of power over others, following a specific form of reasoning (a ‘rationality’) which defines the telos of action or the adequate means to achieve it.” From Thomas Lemke, Foucault, Governmentality and Critique (Boulder CO: Paradigm, 2011), pp. 13-20.

9. Yifat Holzman-Gazit, Land Expropriation in Israel: Law, Culture, and Society (Farnham UK: Ashgate, 2007), p. 88.

10. B’Tselem, ‘Demolition of attackers’ family homes – government policy of vengeance against innocents continues with High Court approval’, 7 October 2015, <http://www.btselem.org/press_releases/20151007_punitive_demolitions_in_jm> [accessed 20 May 2016].

11. Jacob Burns, ‘This Is What Being ‘Tough on Terror’ Looks Like In East Jerusalem’, Huffington Post, 29 October 2015, <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jacob-burns/this-is-what-being-tough-_b_8421196.html> [accessed 20 May 2016].

12. Quoted in Eliav Lieblich, ‘House Demolitions 2.0’, Just Security, 18 December 2015 <https://www.justsecurity.org/28415/house-demolitions-2-0/> [accessed 20 May 2016].