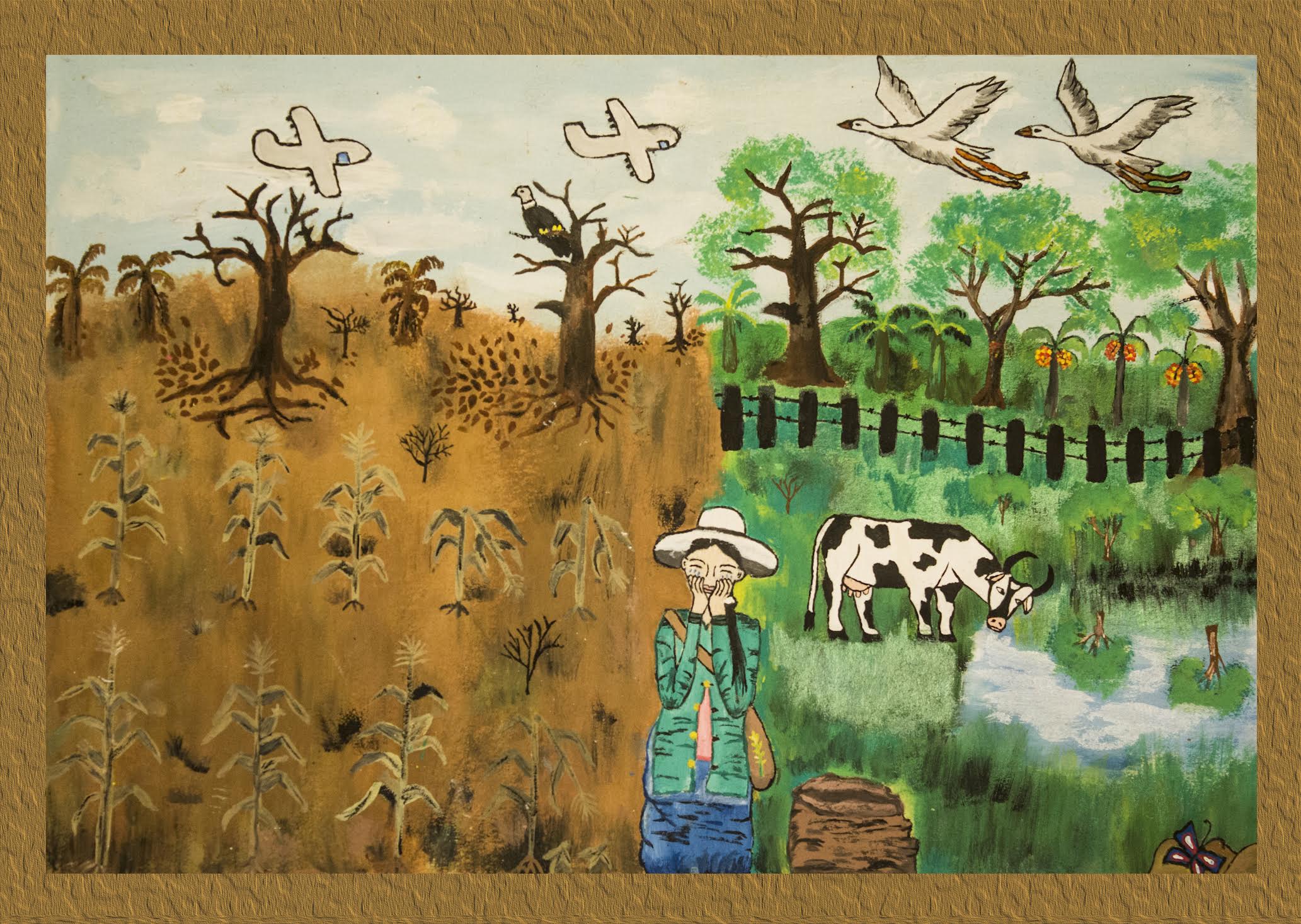

Un mundo sin fin by Yesica Liliana Florez Arroyo, 2014. Photo by Edinson Ivan Arroyo

A world torn in two hangs on a wall in the centre of a small house in the jungle. The painting depicts both halves. The world alive, the world destroyed. And someone, a girl, stands in the middle of the two; her hands over her face, almost covering her eyes. But not quite. In her exposed eyes we can see the terror and sadness of the threshold on which she stands.

Somewhere close by the guerrilla is hiding in the monte, where, as the people around here say, they are the law of the forest.

We are told that there are two guerrilla fronts currently operating here in Putumayo: the 39 from Nariño – we are in their territory now – and the 48 from Caquetá, who reside on the other side of the road that leads to the international bridge/border with Ecuador. Our guide drew a map of their territories on my napkin at breakfast. When he ran out of space on the napkin he switched to my notebook. The frontier with Ecuador runs along the river, and the road (which follows an oil pipeline) serves as a kind of border between the two factions. He told us that it is difficult to go over to the other side of the road. There, weapons, drugs, money and commanders all cross the river to hide away in the jungles of Ecuador.

But here around the farm I am approximately eight kilometres away from Ecuador, visiting fields that were aerially fumigated four months ago. That exact distance – eight kilometres – is significant because now Colombia is legally prohibited from fumigating within ten kilometres of the border. This is because Ecuador filed a lawsuit against Colombia in the International Court of Justice claiming that the herbicide was drifting across the border, damaging their environment and their inhabitants’ health. Fumigation has been the primary ‘tactic’ used to eradicate the coca plant in the US-funded ‘Plan Colombia’. In the court case, Colombia argued that the loss of natural habitat and damages to human health were necessary ‘collaterals’ in the context of their ongoing internal armed conflict. In the end, however, the court ruled that this herbicidal drift was a violation of Ecuadorian national sovereignty, and Colombia agreed to pay 15 million dollars as a form of settlement. The farmers who we interview amidst their dead fields of coca and non-coca are all too aware of this. They say – Ecuador gets millions of dollars, but what do we end up with over here in Colombia? It is our own state that did this to us!

And what does fumigation in the selva of Putumayo look like? Like the painting hanging in the centre of the house. Dried earth with dried leaves, everything is dead or in the process of dying. The forest floor has been bleached out, and left in a twisted pattern of brown earth and pale yellow leaves.

The girl who made this painting of the fumigated world puts me on the back of her motorcycle to go back to her house. She is 15 years old. She wants to go to art school and is happy to hear that I have been.

Later on, down another path, I am standing in front of a large pile of these supposedly criminal leaves. They have been drying for about a day now, lying in the corner of a small wooden structure, a bit like a suspended platform, next to a stream. Now we are about one kilometre away from the border. This is a little laboratory, where the alkaloid used to make cocaine is extracted from the raw leaves. To my left there is a giant, mysterious pile of something brown and desiccated, which I am surprised to learn is entirely comprised of discarded coca leaves. Our new friends don’t want to have their voices recorded – this is not surprising – although, for some reason, they have no problem with being filmed or photographed. We avoid their faces nonetheless. I am fidgeting, not really knowing where to place myself within this illegal activity. My boots are covered in mud from the walk here – I am almost embarrassed to wear them on the platform, like I am dirtying their workspace. I end up sitting on the floor. I don’t know why, it just feels better to be lower – and out of sight. They are paranoid about us for sure. We all just kind of shift around smiling at each other dumbly, like we know how bizarre this is – all being together on this platform, something so normal for them, and so out-of-mind-and-body for us – that somehow we are participating in a criminal activity by just being here.

It is late afternoon, almost the end of the workday. A barefooted man wearing fashionable clothes carries a 50 kilo sack of leaves over his shoulders. He looks very out of place here. Obviously he is strong, but he looks almost glam, with glittery earrings and skinny jeans, next to the other campesinos in stained trousers and muddy boots. I realise that he doesn’t want to wear shoes because the mud will ruin them, and also give away where he has been today. We ask about the process of making the pasta. The leaves that have been drying on the floor are chopped up with a handheld grass-cutting machine; they demonstrate the process for us, and the cameras. The chopped leaves are then dumped into a large drum, which is filled with gasoline. They stew in there, the attendant campesinos stirring the mixture now and again. Eventually, they let the liquid drain out from a spout at the bottom of the barrel. The gasoline and water separate. The gasoline is then discarded into the stream and the remaining water is boiled down to form the coca paste, which is sold on to bigger laboratories to be refined into powder.

At the end of the day we all go to a pool of water that has formed in a depression in the road. We wash our boots, arms, motorcycles, clothes, faces – everything that is covered in mud – mud being the primary evidence of the day’s activities. Again, we are all staring at each other dumbly, smiling, mainly concentrating on the task of washing. But then some vague feeling of normalcy sinks into my stomach through this ritual – like we were never in the campo, never standing next to piles of coca destined to become cocaine, never in illegally fumigated fields, like none of it ever happened. The simple, momentary truth in this pool of rainwater is that the sun is setting over the jungle, and we are bathing with our motorcycles.